Even villains have rights

The "villains' charter" debate has reached Australia, it would seem.

Reviewing Victoria's Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities 12 months after it came into effect, the Sunday Herald-Sun's 'star political reporter' Ellen Whinnett wrote last month that the Charter had been "hijacked by criminals."

Her view echoes Britain's Daily Mail which attacks the UK's 'disastrous' Human Rights Act as turning justice "on its head by putting the rights of criminals above those of the law-abiding."

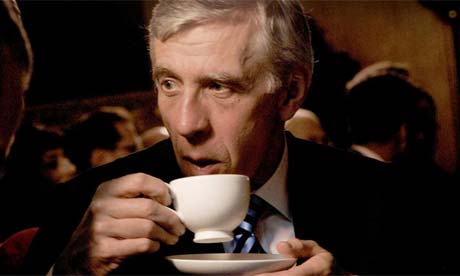

The tabloid was triumphant when, in December last year, UK Justice Secretary, Jack Straw (pictured right), said he had become "greatly frustrated" by the way the 1998 Act had been interpreted by the courts on a few occasions.

The tabloid was triumphant when, in December last year, UK Justice Secretary, Jack Straw (pictured right), said he had become "greatly frustrated" by the way the 1998 Act had been interpreted by the courts on a few occasions.

Straw said he understood why people use the term "villains' charter": "There is a sense that . . . it stops terrorists being deported or criminals being properly given publicity."

Straw has since claimed that he was attempting to defend the Act — Tony Blair's 'proudest achievement' — by addressing its critics.

Nonetheless, he indicated his desire to 'rebalance' the Act with responsibilities such as obedience to the law, loyalty to Britain, staying healthy and educating one's children.

Labour's plans for a 'British Bill of Rights and Responsibilities ' is due to be published by Easter (10 April). Straw has indicated they may add the right to health, education and a clean environment.

Rights protection may be central to Labour's strategy for the next election, due some time in the next 15 months. Tory leader David Cameron welcomes a rights-based stoush.

Labour and the Conservatives fail to understand that rights entail responsibilities, conferring obligations both on the state and all within its jurisdiction. Responsibilities are inherent in rights; the two are inseparable.

To portray human rights as somehow elevating the rights of criminals above others' is to misunderstand human rights entirely. Human rights were declared universal and inalienable by the members of the UN in 1948. Being inalienable means they cannot be taken away, we cannot be separated from our rights. No-one can strip us of our human rights and nothing we may do invalidates them.

This point is important: rights are not just for the good and virtuous. Even the 'worst of the worst' have human rights. They can be punished or imprisoned, but only in accordance with their rights.

The inalienability of human rights guards against arbitrary uses of power. Rights applied equally and invariably to all protect the innocent and lend integrity and transparency to social and political institutions.

Jack Straw would prefer that judges accept government assurances rather than rule in favour of human rights. As Human Rights Watch points out, it is chilling to suggest that a government should decide arbitrarily who doesn't deserve rights.

The villains' rights argument also takes for granted the ways legal protection of human rights serves us all. It is a failure of imagination to overlook how any of us might one day be glad of fair trial rights or protection against deportation to face torture.

It so happens that the deportation of Abu Qatada, a British resident at the centre of this furore, has been approved by the Law Lords. Qatada faces extradition to Jordan, where he has been convicted in absentia of terrorism offences and may face ill-treatment. He has been arrested and detained, pending the outcome of his appeal to the European Court of Human Rights.

Australia lacks either a human rights charter or a regional court of human rights in the Asia-Pacific.

While both major parties in Britain marked the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on 10 December last year by attacking the Human Rights Act, the Rudd Labor Government used the occasion to launch a nationwide consultation on the idea of introducing a statutory bill of rights for Australia.

A vital task for both Governments is to explode pernicious myths and educate the public on how modern statutory rights work. NGO Liberty claims that only 13 per cent of the British public is aware of their rights under the Act.

Too little attention is given to the preponderance of cases in which non-villains call upon the law to protect their rights. As Jack Straw complains to the Daily Mail,

"People don't tend to notice when the Human Rights Act actually does good in helping to defend individuals from unacceptable abuse."

Far from being elitist or remote from daily life, or only serving the interests of 'criminals', Francesca Klug of the London School of Economics demonstrates how the UK Act works to protect 'ordinary' people. Since coming into force in 2000, the Human Rights Act has:

- secured benefits for a disabled child

- given ‘next of kin’ status to same-sex partners and

- initiated a public inquiry into why an Asian prisoner was put in the same cell as a known racist who later murdered him.

Helen Szoke, CEO of the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (pictured right) offers some corresponding examples of everyday Australians invoking the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities:

Helen Szoke, CEO of the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (pictured right) offers some corresponding examples of everyday Australians invoking the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities:

- In one case, an attempt to relocate several young people with acquired brain injuries to aged-care facilities was stalled when advocates caused the hospital to consider its obligations under the Charter.

- Advocates for a woman with a brain injury obtained funding for her medical treatment, thus avoiding painful and costly deterioration of her health.

- A family with a young child was saved from homelessness when advocates showed how a ‘notice to vacate’ limited the family’s human rights.

- A local council was successfully challenged for failing to consider equality and accessibility in service delivery and facilities.

And not one of them was a criminal.